- Home

- T. A. Pratt

Blood Engines

Blood Engines Read online

For Dawson,

my spiritual advisor and minister of war

“Stiffen the sinews, summon up the blood.”

—William Shakespeare, Henry V

1

M arla Mason crouched in the alley beside the City Lights bookstore and threw her runes. The square of royal-purple velvet spread before her on the ground was covered by a scattering of objects—a garlic clove, a withered cigarette butt, a two-headed novelty quarter, fingernail clippings, and the stone from the head of a toad. She studied the pattern the objects made for a long time, then sighed. “It’s no good. This alley isn’t any better than the other two places I tried. I don’t know where all the lines of force are in this city, so I can’t interpret the scatter worth a damn. I thought I could triangulate, but even then it’s too vague. There’s something or someone of power over there”—she gestured vaguely eastward—“but I don’t know if it’s the guy we’re looking for. I’ll have to do a wet divination.” The air smelled faintly of piss and coffee, but not even those familiar urban smells set Marla at ease.

Her companion, Rondeau, stood slurping rice noodles from a waxed-paper box. “I guess guts never lie,” he said, prodding the noodles with his chopstick and plucking out a morsel of chicken. “What are you planning to eviscerate?”

Marla wrapped up her velvet cloth and divining tools and stowed them in a leather shoulder bag. She stretched her arms overhead until she felt her joints pop, then sighed. She’d missed her morning workout, then spent several hours cramped in cattle class during a cross-country flight, and her body was feeling uncooperative. “If I didn’t have such high moral standards, I’d do a human, just because it’s more accurate. Then again, this isn’t my city, so it’s not like I have a responsibility to protect these people.” She was kidding, of course. Murder for mystical purposes incurred a nasty karmic debt, and it was wasteful besides. There were better uses for people. “I don’t know. A cat, maybe. Or a chicken. Nothing too advanced. I doubt Lao Tsung is trying to hide from me.”

“Why do we have to look for him anyway? Why didn’t you let him know we were coming?” Rondeau wiggled his fingers around his left ear. “Ever hear of a telephone?”

Marla snorted. “He’s not the kind of person who has a phone number. There are ways to get messages to him, but it would take a few days, and there wasn’t time for that. I’m in a hurry.”

“I gathered that,” Rondeau said, wiping his mouth with a wad of napkins. “I think my first clue was when you busted into my place, told me to pack a bag, hauled ass to the airport, and hustled me onto a plane. You didn’t even let me sit by the window.” His tone was aggrieved. “My first time on a plane, and you stick me in the middle beside a fat guy with sweat stains. He was smelly.”

“Oh, you noticed that, too? I think it’s your keen powers of observation I value most.”

“You know, I kept hoping you’d volunteer the information, but since you aren’t—what are we doing in San Francisco? What’s so important that you have to see this guy Lao Tsung right now? And why did you need me to come?”

Marla considered. She and Rondeau had saved each other’s lives far more often than they’d threatened them. Keeping secrets was a useful habit, and deeply ingrained, but it paid to remember she did have a few allies she could count on. “It’s Susan Wellstone,” she said, and found herself reaching almost superstitiously for the comfort of the daggers up her sleeves.

Rondeau’s eyes widened. “Really? Her? Of all the movers and shakers in Felport, I never thought she’d be the one to move on you. Gregor, maybe, or Viscarro…” He tossed his empty noodle carton in a garbage can.

Marla shook her head. “Gregor would stab me in the back if I ever gave him the chance, and Viscarro will be there to steal the jewels and gold fillings off whatever corpse falls first, but Susan’s the only one willing to make an opportunity, instead of just waiting for one. She knows that if she loses, I’ll destroy her. But she’s a perfectionist. She doesn’t intend to lose. She means to overthrow me.”

Rondeau frowned. “So why isn’t she hanging upside down in a vat of acid right now? What are we doing on the other side of the continent? You can’t be running away.”

“I better not have heard a little upward lilt at the end of that last sentence, Rondeau,” Marla said, crossing her arms. “I know you weren’t asking if I’m running away.”

Rondeau held up his hands. “I know better. I’ve seen you duck from the occasional social obligation, but never a fight.”

“Yeah, well.” Marla ran her hand through her short hair, bits of scalp flaking away. She’d never had dandruff in her twenties. Getting older had its advantages, but dandruff wasn’t one of them. “This isn’t a fight I can win, not head-on. Susan’s planning to cast a spell to get rid of me, but she hasn’t thought through all the implications, and her spell’s going to wind up wrecking my city, too. I can respect her desire to kill me—she wants my position, and she knows I’m not about to retire anytime soon—but I can’t forgive her for risking Felport.”

“So Lao Tsung can help you stop Susan’s spell?”

“Lao Tsung knows where to find something that can help me. The Cornerstone. But don’t go throwing that around to the local sorcerers.”

“Ah,” Rondeau said. “An artifact? I hate artifacts. Things shouldn’t look at you, and that old weird stuff always seems to be paying attention.”

“I thought you liked attention.”

Rondeau rolled his eyes. “We’re under a time limit here?”

“One that gets shorter every minute we stand here talking. Have I satisfied your curiosity? Can I get on with saving my city and my life now?”

“You never told me why I’m here. You could’ve left me behind with Hamil to, like, muster the defenses or something. You might be the first one up against the wall when the revolution comes, but Hamil and I won’t be far behind.”

“It’s…not like that,” Marla said. Explaining the nature of Susan’s spell would be too complicated, and it wasn’t something she was comfortable thinking about, beyond taking the measures necessary to thwart it. “Besides, I need you here to lift heavy things, guard doorways, and deal with any other shit I’m too busy to bother with.”

Rondeau grinned. “A man likes to feel useful. Lead on.”

“Do you think we can find a live chicken around here?”

“Maybe if we search high and low.” They set off toward the hanging paper lanterns, pagoda storefronts, and crowded afternoon sidewalks of Chinatown.

“I don’t know why Lao Tsung decided to live in this shithole quakemeat city,” Marla said. “He came here to find the Cornerstone, but then he stayed.”

Rondeau grunted. “We’ve only been in San Francisco for an hour. You hate it already?”

Marla spat on the street. “Pretty white city by the bay, my ass.”

“Don’t forget ‘cool, gray city of love.’”

“Yeah, I feel the love,” Marla said, stepping over a pile of dirty stuffed animals someone had left on the sidewalk.

“I think it’s nice. You’re just jealous because we don’t have cable cars back home.” He glanced up a side street. “Not that I’ve seen a cable car yet.”

“It’s January,” Marla said. “There should be snow in January. A little fog is no substitute. I feel out of place. Far from my center.”

“Well, yeah. It was, what, your second time on an airplane? I thought you were going to strangle random strangers during the layover in Denver. Haven’t you ever taken a vacation?”

Marla laughed, and Rondeau nodded. “Me neither. This is my first one.”

“This isn’t a vacation. It’s a matter—”

“Of life, death, and destruction, I know. That doesn’t mean I can’t take

in the sights, right? What’s the point of staying alive if you don’t live a little?” They entered the closely packed streets of Chinatown, where off-season tourists wandered among the food stalls and the stores, picking through wares spilling out onto the sidewalks. There were tanks full of tightly packed wriggling fish, and wooden crates filled with strange fruit. The street signs had both English names and Chinese characters, and there were lots of fanciful architectural touches—faux pagodas made of wood on top of buildings, gold-painted facades, bamboo fences. “I love this place,” Rondeau said. “There’s nothing like this back home.”

“Because our city never had a ghetto for underpaid, persecuted immigrant Chinese laborers in the 19th century,” Marla said.

“I suspect San Francisco won’t be offering you a position as a tour guide anytime soon.”

“I distrust, on principle, any city that encourages me to leave my heart behind when I go.” Marla abruptly stopped walking, and Rondeau almost bumped into her. “Hmm, there it is again.”

“What?”

She waved her hands. “Whatever the divination was indicating. A field, a hum, a vibration. Something. Not far from here.”

“I don’t hear any hum,” Rondeau said.

“Come on, it’s this way.”

“Ah,” Rondeau said, following her down the block. “Might I suggest that we, say, ignore whatever magical you-don’t-know-what we’re now moving toward? Why borrow trouble?”

“I cause trouble, I don’t stumble into it.” Not precisely true, but the plane flight—and the necessity of flight—had made her cranky, and she’d always had a curious streak anyway. “Besides, maybe this magical something-or-other is what I’m looking for, the Cornerstone, and I won’t need to find Lao Tsung at all.”

“Right,” Rondeau said. “Because we’re in a Charles Dickens novel, and coincidences like that actually happen.”

After about a block of walking, Marla stopped. “There.”

“What? It’s just a booth selling bootleg Jackie Chan videos—Oh. You mean that.”

There was a folded space there, between a tea shop and one of the area’s many jewelry stores—Marla could just see the shimmer. If there was a shop inside that shimmer, it wasn’t one meant for ordinary tourists. “Want to go in?”

“I thought you just wanted to buy a chicken and find a nice quiet alley to scoop out its guts. Why do you want to mess with the local mojo?”

“Lao Tsung is a sorcerer,” Marla said reasonably. “Maybe another sorcerer will know where to find him.”

“Sorcerers are all at least half crazy by definition,” Rondeau said. “Present company excepted. So what if we get, like, attacked?”

Marla shrugged. Being attacked wouldn’t be so bad. Right now, loath as she was to admit it, she was afraid. A fight would at least take her mind off Susan’s plot, flood her with adrenaline, and give her a workout—physical or metaphysical, either would be welcome. “If we’re attacked, try not to get in the way.”

“I bet this will be just like Big Trouble in Little China,” Rondeau said. “Weird herbs everywhere, stuffed alligators hanging from the ceiling, and a guy shooting lightning bolts out of his eyes.”

“I’m trying to decide if that was racist or not.”

“What?” Rondeau said. “Me, or the movie?”

Marla ignored him, glancing around. There were people watching her, of course, or at least looking in her direction—it was a busy street. Ah, well. Fuck it. She grabbed Rondeau’s wrist and slipped around a table of bootleg videos, into a folded place in the world. Into a sorcerer’s den.

They emerged into a large room with a décor halfway between herb shop and high-tech. The floors, walls, and ceiling were pristine white, with subtle curves instead of hard-angled corners, and tall dark wood shelves butted up against one another at strange (and probably occultishly significant) angles, crammed with tins, bottles, jars, and plastic bags, most of which appeared to be filled with various kinds of dried vegetable matter. Marla wasn’t interested in herbal magic—she’d never bothered overmuch with any herbs you couldn’t grow in a container on a fire escape or find sprouting wild in a railroad yard. The air should have been a riot of odors, but there was a curious neutrality of odor instead, with just a hint of the antiseptic.

A long stainless-steel counter stretched the length of the back wall. A concealed door behind the counter swung open, and an elderly Asian gentleman in a dark robe emerged, followed by a far less graceful young man, presumably an apprentice. Marla caught a brief glimpse of the space behind the door, where someone lay naked on an examining table, red welts across his skin.

The door swung shut, and Marla turned her attention to the men behind the counter. The apprentice was actually a woman, dressed in boy-drag. She’d done an excellent job, but when Marla first moved to Felport, she’d found work waitressing at various bars in the less-than-respectable part of town, and still had a good eye for costume. She was in San Francisco, where drag was king, so she probably shouldn’t be surprised. Odds were the old guy was the master, and the young girl was either apprentice or servant. The old man spoke to her in Chinese—Cantonese, probably, the prevailing dialect in Chinatown—but Marla shook her head.

“Nope, sorry. I can do English and I can get by in French, and my friend here can speak Spanish and knows a few swear words in a language that predates the fall of Babel, but neither of us can speak any kind of Chinese.”

“What do you want?” the girl asked, in clear, unaccented English.

Marla looked at the master. He was expressionless, but she suspected he could understand English as well as the girl could. “I need information.”

The old man shook his head and bowed a fraction of a degree.

“We sell herbs, not information,” the apprentice said. She was trying to watch both Marla and Rondeau, which was difficult, as Rondeau had begun absentmindedly wandering around the shop, prodding at things.

“I’m looking for a man named Lao Tsung,” Marla said.

The old man sniffed. The apprentice sneered, no longer pretending to be polite. “And you think all Chinese people know one another?”

Marla rolled her eyes. “Look, where I’m from, we keep track of all the important sorcerers who come around. Lao Tsung’s been living in the city for years, and he’s got power. He’s not actually Chinese anyway. He’s a very long-lived Mesopotamian, if that makes you feel any better. I figured you might know where he is, that’s all. If you can’t help me…”

The old man looked meditatively at the ceiling. “One thousand dollars,” he said, his English crisp and faintly British. “That is the price of the information you seek.”

Marla frowned. “Look, I could cut open a chicken and stir around its guts and find Lao Tsung—I’ve got the gift of haruspexy. I just thought it would be less bloody to ask the locals. I don’t want to step on any toes, I just want to do my business and leave.”

“Haruspexy will not work. Try it if you want, but don’t come back after. Already you waste our time. One thousand dollars.”

Marla sighed and called Rondeau over.

He was holding half the money, which was perhaps a mistake, but he’d insisted. If Marla died in an earthquake, he’d said, how would he afford to get home? He gave the bills to Marla, and she passed them on to the apprentice, who examined them and nodded.

“Lao Tsung is dead,” the old man said, without apparent pleasure.

“Bullshit,” Marla said. “He’s been alive for centuries, he came here specifically to get his cancer healed, and it worked. How can he be dead?”

“The answer to that question will cost one thousand dollars.”

Marla was over the counter before the old man could even step back, pressing a dagger into his belly. He opened his mouth—presumably to loose some spell—and Marla shoved a wad of cash between his teeth, silencing him. “As you can see, it’s not about the money. I just don’t like having my time wasted. And Lao Tsung was a friend.”

&n

bsp; The apprentice was speaking quietly to herself, and Marla sighed. “Rondeau?”

“Yup,” he said, and drew his butterfly knife, flipping it open with the ease bred of a lifetime on—and under—the streets. “Okay, so be quiet, or I’ll have to cut your throat or something, and I just got this suit, so that would suck for both of us.”

The apprentice stopped talking. “You are not sorcerers,” she said. “You are thugs.”

“There’s a time and a place for magic,” Marla said, “but it’s a bad idea to get too dependent on the abracadabras.” She returned her attention to the old man, who did not look terrified, or angry, or anything at all; his expression was impossible to interpret. “I’m going to take this money out of your mouth, and give it to your apprentice, and then you’ll consider yourself paid in full, and tell me everything I need to know about Lao Tsung, okay? And if you get itchy for revenge, let me tell you who I am—I’m Marla Mason. I run the city of Felport, and if you haven’t heard of me before…well, I can make a name for myself on this coast by doing something incredibly nasty to you. But like I said, I just want to do my business and be on my way. Agreed?”

The old man nodded.

Marla took the wad of paper from his mouth and handed it to the assistant, who began straightening the cash on the counter, spreading the bills out, smoothing the wrinkles, making piles. The master must be a disciplinarian son of a bitch, Marla thought. “So,” she said. “Lao Tsung.”

The old man mumbled something in Chinese.

“As we told you, Lao Tsung is dead,” the apprentice said, without looking up from the money, apparently unconcerned with Rondeau and his knife. “He was killed this morning by frogs.”

Marla repeated those words to herself—“killed this morning by frogs”—considering the possibility that it was some idiom translating badly. “He was killed by French people?” she said at last, frowning.

The apprentice looked at her, bored. “No. By frogs. Hop, hop? Frogs. Lao Tsung lived in Golden Gate Park, and he was discovered this morning covered by small golden frogs. The frogs hopped away, and no one tried to stop them—we assume they are poisonous. There are frogs in the rain forests venomous enough to kill a hundred men.”

Do Better: Marla Mason Stories

Do Better: Marla Mason Stories Spell Games

Spell Games Lady of Misrule (Marla Mason Book 8)

Lady of Misrule (Marla Mason Book 8) Bride of Death (Marla Mason)

Bride of Death (Marla Mason) Dead Reign

Dead Reign Blood Engines

Blood Engines Queen of Nothing (Marla Mason Book 9)

Queen of Nothing (Marla Mason Book 9) Poison Sleep

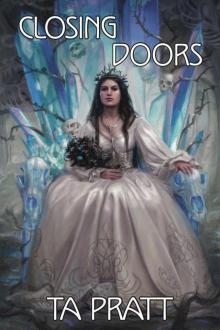

Poison Sleep Closing Doors: The Last Marla Mason Novel

Closing Doors: The Last Marla Mason Novel